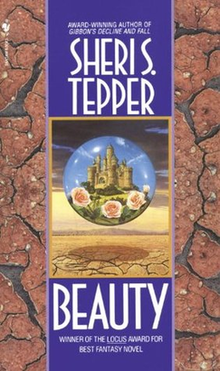

Beauty (Tepper novel)

| |

| Author | Sheri S. Tepper |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Joseph Scrofani |

| Language | English |

| Published | 1991 |

| Publisher | Bantam Doubleday |

| Publication place | United States |

| ISBN | 9780385419390 |

Beauty is a fantasy novel by Sheri S. Tepper published in 1991 that won the 1992 Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel.

Summary

[edit]Beauty, the daughter of the Duke of Westfaire, finds a letter from her mother, who mysteriously disappeared when Beauty was an infant, and learns of a curse that will occur on her upcoming sixteenth birthday. Using magical items that she constructs with thread left to her by her mother, Beauty evades the curse, which instead falls on her half-sister. Beauty is abducted by a time-traveling crew that came to film the curse falling on the castle, and they take her to a dystopian future.

The film crew and Beauty steal a time-machine and travel back to 1991. The camera operator, Jaybee, kills Bill, the scriptwriter, when Bill tries to protect Beauty, then Jaybee rapes Beauty. Beauty uses the magic boots she had made to work her way back to her own time, only to find the Black Death has struck the area in her absence. Disguised as a boy, she is taken in at Wellingford House as a stableboy. Beauty soon realizes that she is pregnant. She returns to Westfaire to alter her appearance, then returns to Wellingford House to lure one of the sons to marry her. She marries Ned and gives birth to a girl, but Beauty sees Jaybee in the infant Elly's eyes and feels revulsion toward the baby.

Out riding one day, Beauty encounters Giles, who had been one of her father's men-at-arms and had been sent away by the family priest who had observed the growing affection between Beauty and Giles. Their romantic reunion goes awry when Beauty explains that she is married now. Distraught at losing Giles again and unhappy in her marriage, Beauty puts on her magic boots and tells the boots to take her to her mother.

The boots take her to a land that she learns is called Chinanga. Traveling on the boat that rescues her, Beauty encounters Carabosse, the fairy who had laid the curse. Carabosse explains that she is trying to protect Beauty from the Dark Lord, the evil power. They encounter Beauty's mother, Elladine, who had been trapped in Chinanga. When a ceremony dissolves the imaginary land of Chinanga, Beauty, Elladine, and Carabosse travel to Ylles, the fairy land, where Beauty learns how to use her fairy powers. While there, Beauty helps Thomas the Rhymer escape. Carabosse tells Beauty that she has seen in the future that magic disappears, and that to preserve it, a seed was planted in Beauty for safekeeping.

Beauty moves back and forth between her time, the future, Ylles, and the realm of the Dark Lord. She rediscovers Giles, meets her now-grown daughter, rescues her adolescent granddaughter, encounters her enchanted great-grandson, and takes vengeance on Jaybee. Horrified at how the future has destroyed magic and beauty and nature, she uses her fairy magic to save some of every type of bird and animal and fish and insect, every tree and flower and herb.

Themes

[edit]Beauty presents a narrative in which the world is doomed and Beauty's goal is preserving the world for the future. Tepper uses the Sleeping Beauty framework to explore issues of sexuality and ecology for Beauty herself and the impact of those issues on a global scale. Her dystopian future shows a world with no quality of life; global biodiversity has been sacrificed to feed an overpopulated world. Magic and beauty are lost as time and technology progress.[1]

Robert Collins, writing in the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, characterizes the novel as ecofeminism, with Beauty as an icon of the green movement. Through the eyes of Beauty, the medieval past is positioned as a vision of natural beauty and contrasted to an "apocalyptic ugliness" of a world degraded and destroyed by "rampant humanity".[2] Tepper's ecological theme is expressed through Beauty's description of the conceptual "gobble-god":[3]

"We have been thwarted at every turn by god. Not the real God. A false one which has been set up by man to expedite his destruction of the earth. He is the gobble-god who bids fair to swallow everything in the name of a totally selfish humanity. His ten commandments are me first (let me live as I please), humans first (let all other living things die for my benefit), sperm first (no birth control), birth first (no abortions), males first (no women's rights), my culture/tribe/language/religion first (separatism/terrorism), my race first (no human rights), my politics first ... country first ... and, above all, profit first. We worship the gobble-god. We burn forests in his name. We kill whales and dolphins in his name .... we set bombs in his name."

Tepper weaves multiple fairy tale narratives into the plot: Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, Snow White, The Frog Prince[4] and Tam Lin.[5] Starting out as the heroine, Beauty transitions into the roles of fairy godmother and then to ancient grandmother, and recognizes the roles of her descendants as parts of fairy tales from her time in the future. The idealistic nature of fairy tales is contrasted with the realistic form of love that Beauty and Giles find in their old age.[4]

Reception

[edit]Beauty won the 1992 Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel, and was nominated for the Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Adult Literature. It was a preliminary nominee for the 1992 Hugo Award for Best Novel.[6]

Lauren Lacey says of Tepper's Beauty: "her focus on bringing the tales together rather than on encouraging the proliferation of their possibilities leads to a damaging sense of narrative closure."[4] A review in The Kingston Whig-Standard says Tepper "takes the two-dimensional, symbolic characters of a fairy tale and makes them real by giving both them and their stories depth and historical detail."[7]

Kirkus Reviews is generally negative, saying "Tepper can't decide whether to warn against a gathering spiritual darkness, lament the collapse of an aesthetic ideal, or thunder against global eco-disaster."[8]

References

[edit]- ^ Tiffin, Jessica (2009). Marvelous Geometry. Wayne State University Press. pp. 173–177. ISBN 9780814332627.

- ^ Collins, Robert. A. (1997). "Tepper's "Chinanga": A Parable of Deconstruction". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 8 (4 (32)): 464–471. ISSN 0897-0521. JSTOR 43308314.

- ^ Raddeker, Hélène Bowen (November 2009). "Eco/Feminism and History in Fantasy Writing by Women". Literary and Political Reviews. University of Western Australia, Centre for Women's Studies.

- ^ a b c Lacey, Lauren J. (December 7, 2013). The Past That Might Have Been, the Future That May Come: Women Writing Fantastic Fiction, 1960s to the Present. McFarland. pp. 51–55. ISBN 978-1-4766-1430-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Attebery, Brian (1996). "Gender, Fantasy, and the Authority of Tradition". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 7 (1 (25)): 51–60. ISSN 0897-0521. JSTOR 43308255.

- ^ "Title: Beauty". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "Bookstand". Kingston Whig-Standard. May 23, 1992. ISSN 0839-0754.

- ^ "Kirkus Reviews: Beauty". Kirkus. May 10, 2010.